But this narrative only stands if you believe that “real” science can’t happen outside of legitimizing institutions. Or you can consider the rivalry that motivates the self-serving claim, which I’ve seen put forward by white-coats at various psychedelic science gatherings, that psychedelic science stopped with the scheduling of LSD and related compounds in the ‘60s and early ‘70s, and only started up again with the renaissance man Roland Griffiths or, if they are being fair, Rick Strassman. One example of this tension is a topic that frequently came up at the Chacruna Institute’s Religion and Psychedelics Forum where I recently moderated some panels: “What is “mystical experience”? And if there is something like mystical experience, is it really translatable to data, as the popular Mystical Experience Questionnaire implies? The labs at Johns Hopkins and NYU dig this stuff, but other psychedelic scientists-for some very good reasons-think these measures open the door to supernatural obscurantism.

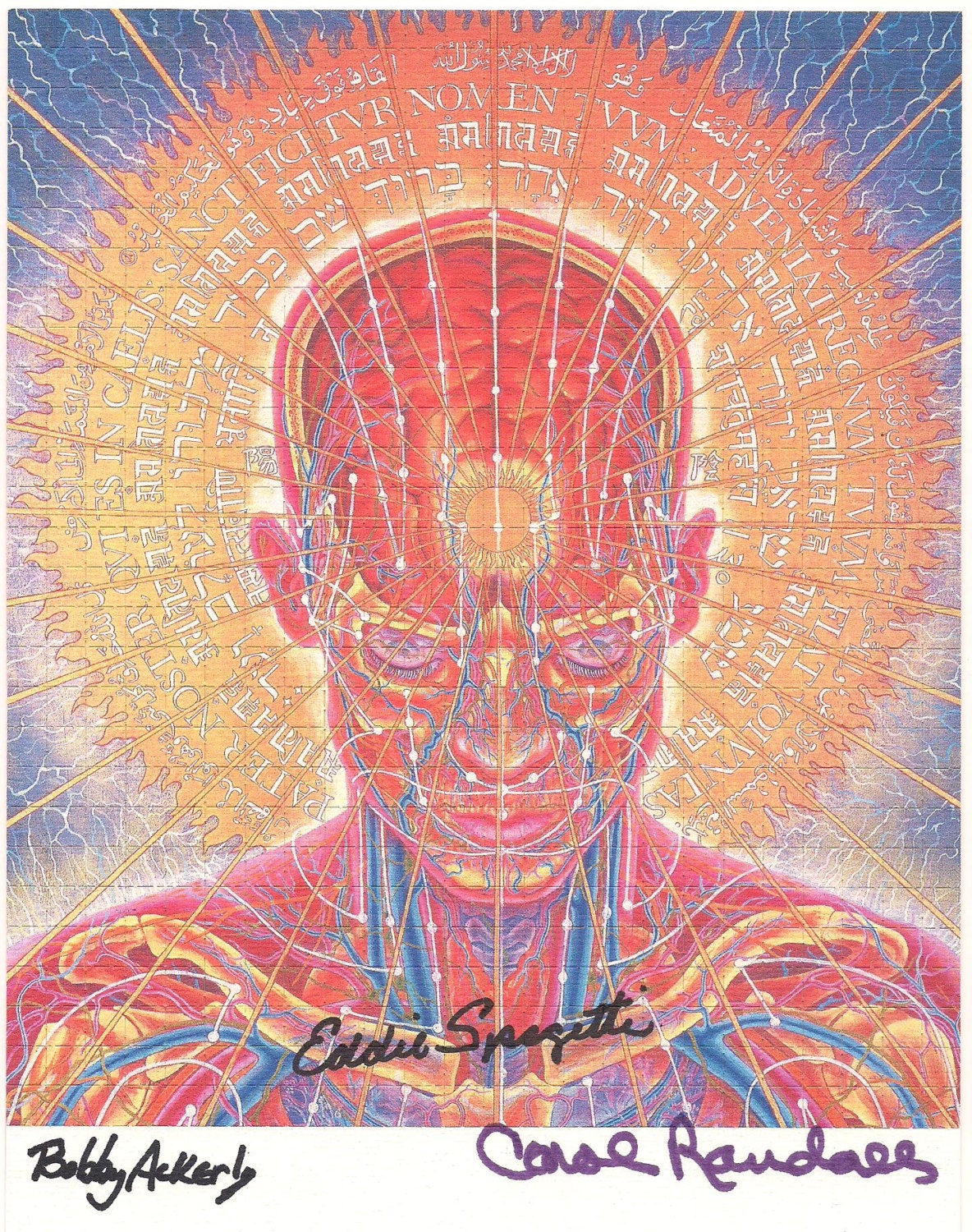

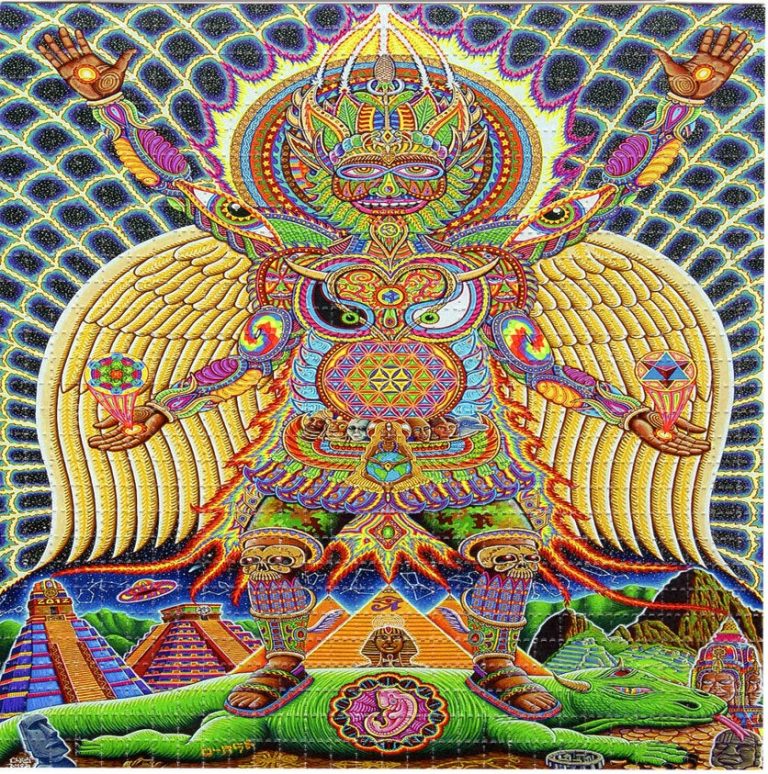

LSD BLOTTER ART SASHA PROFESSIONAL

Here too we have seen various professional bodies and discourses, with rivalries between them, attempt to establish their dominance over the knowledge basis of psychedelics, partly with an eye to extract value for a hungry pharmaceutical and mental health industry. This therapeutic land rush is in turn dependent on the “return” of psychedelic science and clinical research. Recent debates about governance and abuse within underground therapy networks, however vital and deserved, must also be seen in light of this larger movement towards professionalization.

LSD BLOTTER ART SASHA LICENSE

In the domain of mental health, professional bodies-including credentialed therapists and the institutions that license them-are now directly competing with already existing underground therapy networks, whose days may well be numbered. Who gets to speak for psychedelics, and in what tongue? This struggle is partly an institutional one, which is why it feels so real-this isn’t just individuals arguing, but whole sectors of society. A lot of psychedelic discourse today is driven by an overt or covert struggle over legitimacy. Why? For the simple reason that, beyond the cliches that imprison the substance, LSD is not currently subject to capitalist narrative capture. But if you climb on the beast’s back, and embrace the positionality of the acidhead, you are gifted with a particularly illuminating perspective on the current psychedelic scene. We forget that the elephant in the room can roar like a cosmic hurricane. In an era of “sacred plants,” of commercial formulations and utterly manageable microdosing, LSD the Mighty has drifted to the periphery of our consciousness, its teachings discursively marginalized, almost repressed, even as its tropes are regurgitated as Haight Street kitsch and corny vanity blotter. If you tune into the journals and journalism of today, or follow the changing waves of psychedelic discourse, you will note that LSD has taken a back seat in academic research, therapeutic protocols, and the cultural imaginary.

After all, given that blotter only really takes off in the late 1970s, its story lies mostly outside the conventional ‘60s narratives of LSD.īut if LSD never stopped influencing culture, and if the drug remains a popular goodie-dependably available in underground drug markets, at festivals, and on drug-nerd dark webs-why do I call LSD the elephant in the room? Here’s why. What interested me were the elusive nitty-gritty details of manufacturing practices, drug distribution, and the fascinating and mixed motivations of the artists, producers, printmakers, and dealers who developed the blotter format into a unique mode of art-or iconography, or branding-whose images reflect all manner of aesthetic, cultural, spiritual, and prankster attitudes.įollowing a space opened up by Jesse Jarnow’s book Heads, my research put me in touch with the concrete social reality of the acid underground, which persisted whether or not the drug was in the papers, underground or otherwise. I largely ignored these stories along with discussions of acid ideology, except to the extent that it helps explain the motivation of blotter makers. Hofmann’s bike ride, MK-Ultra’s miseries, Michael Hollingshead’s mayo jar, Kesey’s Kool-Aid, Manson’s mind control, Jerry’s bone-dancing congregation.

In a way we already know the story of acid, which can seem superficially settled, even rote, its signature events and colorful characters trotted out like clockwork in many potted histories online: Dr.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)